Articles About Briolettes, Gems and Minerals

Briolette Diamond: Old Glories, by David Federman, Modern Jeweler, May 1999

Briolette Diamond: Old Glories

by David Federman,

Modern Jeweler, May 1999

To hear moderns talk of diamonds, you might think their only job is to strike you dumb with their light. Well, the briolette diamond is a reminder that once not so very long ago the world expected diamonds to catch eyes, not blind them. Three hundred or so years back, the beauty of this gem was more delicate, one you might describe as lunar rather than solar. Sure, stones had that legendary glow. But their radiance stayed contained within the diamond like the light of a full moon rather than bursting its seams like light from a noonday sun.

Suddenly, in an age which rates highest the brilliance of zero-cut and hearts-and-arrows rounds, designers and jewelers alike are also rediscovering the more muted 17th century aesthetic for this gem. That's when cutters started to produce cylindrical tear-drop shapes entirely covered with triangular (and occasionally rectangular, even rhomboid) facets that made them seem like tiny crystal chandeliers. These diamonds are called briolettes and their charm made a virtue of necessity.

Don't judge this aesthetic by modern standards. It isn't fair to do so since the modern round-brilliant and its forerunners such as the cushion-cut "old miner" didn't yet exist. Design features such as tables and crowns were still in the future. The idea of proportions was yet to be invented. Instead, cutters were taught to stick closely to the original contours of the rough, refining the shape and placing facets everywhere to free as much of the light locked inside stones as possible. But the light wasn't meant to obscure the facet designs Cutters sought a balance between light and line.

Depending on the shape of the rough, briolettes ranged in final form from bulbous to elongated. Existing technology permitted little more than crude shaping. Aesthetics of the day demanded little more than the glitter these artisans achieved. "Everything about these stones was individualistic and improvised. Anything went with regard to shape. And there was no fixed number or size of facets. The cutter was allowed free reign," says antique cuts specialist Pankaj Surana of Diagems in New York as he examines a parcel of briolettes made in India a few centuries ago.

No doubt, the seemingly haphazard workmanship of these briolettes which fills Surana (and this writer, too) with wonder would horrify cutters today-even those working in Diagem's Bombay factory where briolettes are a specialty. Of course, these are a highly modernized version of this cut. "Today the cutter of briolettes would probably fear for his job if he cut stones so free-form in their shaping and faceting," Surana concedes.

Nevertheless, the modern briolette allows cutters lots of liberties and preserves the play-it-by-ear spirit of antiquity. As a result, these elegant throwbacks are enjoying the strongest of several revivals in the past two centuries. This time, demand is keeping hundreds of cutters busy in India.

PRESERVING THE PAST, HONORING THE PRESENT

By the late 17th century, the briolette was a passing fancy as cutters embraced

the precursors of the modern round-brilliant and bought this style to recut it.

Within 50 years, the briolette was an endangered species. Sadly, appeals to halt

the carnage of conversion from old to new cuts from the period's top jewelers

like London's David Jeffries went ignored until Victorian and later Art Deco

designers fell under the spell of the briolette.

Recently, the briolette has once again gone from lost cause to cause celebre as influential designers such as Alex Sepkus in New York and Cynthia Bach in Los Angeles have become very vocal advocates of this and other antique cutting styles. But the briolettes they use pay homage as much to the present as the past. True to the past, there is still a lot of leeway as to number of facets and their placement. But true to the present, symmetry is important. "The rounder the shape and more precise the faceting, the more desirable the stone," says Surana.

Since most briolettes end up dangling in earrings or pendants, "Pay close attention to the positioning of drill holes," warns Jeff Feero of Alex Sepkus. "If the hole is off center and the wall weak, the stone may not be strong enough to withstand twists and turns of the wire in normal wear."

Currently, there are three color classes of modern-day briolette in use among designers: whites (mostly G to I), light yellows (top to medium capes), and browns (cognacs). Demand is concentrated mostly in whites from a half to one carat in size costing generally between $750 and $1,000 per carat. However, prices between $400 and $600 per carat for cape-ish and cognac colors in these sizes is starting to draw attention to them also.

(Return to the top of this page)

Return to Elegance: Steve Green and Brilliant Briolettes

by Andy Oriel,

Lapidary Journal,

September 1998

Times are good. Champagne and caviar are "in", gasoline is cheap, and classic elegance is making a comeback. In keeping with that trend, jewelry designers and their customers are looking for tasteful settings and stones that are comfortable to wear, of lasting quality, and that won't be autre next week.

The answer to all those requests may be found in a little-known gem called a briolette. According to Denver lapidary and gem dealer Steve Green of Rough and Ready Gems, its muted expression of luxury is in the same league as a classic strand of pearls for a fraction of the price.

What is a briolette? The Gemological Institute of America's dictionary defines it as "a pear or drop-shaped gemstone having its entire surface covered with small triangular facets." To you and me, the 800-year-old cut looks suspiciously like a crystal plucked from a chandelier, and has the same associations with romance, aristocracy and the finer things in life.

For Green, who began his career while on a 50,0000-mile motorcycle trip through South America, the design is also an opportunity to make inroads into the rough-and-tumble gem market. And because he grew up in Mexico, with its long tradition of craftmanship, he saw the opportunity to start a cottage industry there to cut the new/old stone, updating it slightly for this fin-de-siecle.

Though he doesn't do the faceting himself - only the preforming - Green has worked tirelessly to make the rediscovered stone a success.

For those who do take the challenge, the briolette opens a whole new approach to gemstones. Instead of being oriented to one point - the table - they can be viewed from any direction, making them ideal for pendants and earrings. And because they are hung by their tips, their voluptuous forms, like raindrops caught in midair, can be admired as they came off the wheel.

It has been said that elegance is good taste plus a dash of daring, and the briolette has both. If jewelry conveys a message about the wearer, then briolettes fairly shout savoir faire. But don't worry, it's no more for snobs than is cafe au lait and even cost-conscious gem lovers can enjoy the promise of inexpensive elegance.

OUT OF NOWHERE. It was 1979 and Steve Green was a bearded hippie stranded on Argentina's barren Patagonia plateau. Miles from anywhere, he was sitting on a BMW motorcycle loaded down with provisions, spare tires, and some bottles of bootleg liquor. But no fuel. Patagonia runs on diesel.

"I had separated from my partner so I was alone in the middle of nowhere," recalls the 42-year-old from his suburban home west of Denver. "I remembered that I had a motorcycle cover and some tent poles, so I made a makeshift sail and attached it to the bike. I literally sailed 40 miles in howling wind until I found gas."

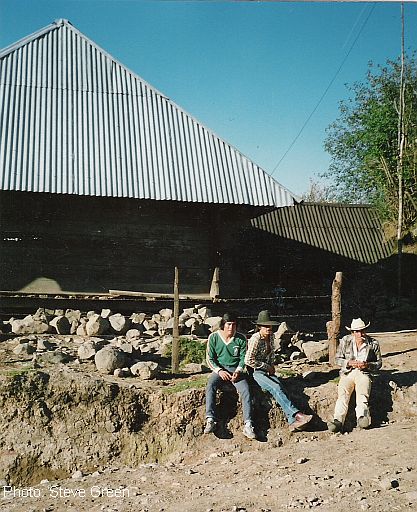

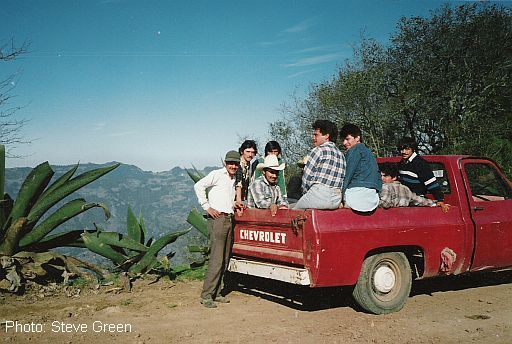

Showing photos from the trip, which covered 50,000 miles in 18 months, Green is proud of the stubborn self-reliance he cultivated along the way.

"I have a very unique product because I made it that way," he says, sitting at his kitchen table with his wife, Marcia, and son, Alex. "I'm not the only person in history to cut the briolette, but now, for whatever reason, I'm the only person to make it in 50 different materials, in matched pairs, and in different shapes and sizes.

"Affordability is a big factor, too. Up to now, German-cut briolettes were very good and very expensive, and Indian-cut stones were cheap, but poorly made. By preforming the stones myself and having them cut in Mexico, I can keep quality up and prices in the middle."

While Alex sits on his daddy's lap and stacks boxes of briolettes like blocks, Green pulls out a favorite in imperial topaz and turns it between his fingers in the light.

"The movement in them is dazzling," he says. "They really show off a stone in a way that nothing else can because the light goes through and reflects out of them. They're like three-dimensional drops of color."

Green is very well aware of the secret of his success. "Everyone can see that they're different," he says, in an exacting tone that reveals his scientific background, "but I saw potential in them and did research on how to cut them and set them - that was the key and I spent a lot of time talking to jewelers and customers, educating them about the stones and how to set them.

"Four or five years ago I was just one of a hundred guys selling the same things at Tucson, and the competition was fierce. But I saw a market, did my homework, and now, it seems like all of a sudden I have a viable product, but it's been over 10 years in the making."

STONES CON BRIO. They're called briolettes from the French word brio, for vivacity or spirit, and they certainly have that. They are not the rarest gemstones, or the most difficult to cut. But they are extraordinary, and have the credentials to prove it.

The Briolette of India is, in fact, the oldest diamond on record and the first recorded briolette, dating back to the time of the Crusades between 1122 and 1200. If not a legendary cut, the design is at least classic, showing a perfection of form, technical prowess, and a timelessness that makes modern gems seem wet behind the ears.

Over the 800-plus years that the cut has been known, its popularity has waxed and waned as many times as hemlines have gone up and down. Most recently, popularity rose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when the cut was used in long, delicate pendants. Before that, they were popularized in 18th-century France, where they were considered the epitome of refinement. Strictly speaking, the design is a modified double rose cut with a pointed tip, a rounded bottom, and four to seven rows of facets in between. But within those parameters there are many variations, including impossibly long and thin shapes, plump round ones, and even what Green calls "unfaceted briolettes" that break the boundaries.

"The nice thing about briolettes is that you can use uncommon materials, or you can make common materials appear less common.

Because briolettes react differently to light than traditional cuts, he says different shapes and proportions are especially well-suited for certain stones. Darker stones can be cut thinner, for example, and lighter stones fatter, but that is just the beginning.

"I basically cut two different kinds of briolettes. Most have a round cross section, but some have a flattened, oval cross section like a pumpkin seed, but not that thin. Sheen stones and stars work best in fat, round shapes. The flattened ones work much better for strongly dichroic materials like iolite or tourmaline. You can fine-tune the color axis so it shows up best along the flattened plane. It also works well with opal for the same reason, and they really hang nicely on the body."

If briolettes are easy to look at, they are hardly easy to make. "Briolettes are not a uniform product, they're not like a 5x7 oval," Green says. "They are difficult to make because each and every one requires a lot of attention."

Working in his garage workshop, surrounded by his collection of motorcycles, Green preforms a tourmaline into a sort of zeppelin-shaped drop. One down, 999 to go before his upcoming trip to Mexico. He goes four or five times a year, returning with a case of finished stones.

Steve and his KLR

enjoying a little warmth

on a Colorado winter ride.

"My life is punctuated by trips to Mexico," he says as he grinds. "A lot of people don't know that Mexico has an established cutting industry that was set up for opals and amethyst. It used to be that tourists would drive to Mexico and come back with an opal or a synthetic alexandrite set in a gold ring. That all changed in the '70s, but the cutting industry was still in place."

THE MEXICAN CONNECTION. Green's Mexican connection and entrepreneurial spirit both began when his family moved there from New York when he was 10 years old. On excursions back to the States, he would bring sandals, blankets, and serapes to sell to New Yorkers. Returning to Mexico, he took bags of SweetTarts and Milky Way bars to sell to his teenage expatriate friends.

Green returned to the States to study biology and chemistry at Denver University. Shortly after graduating in 1977, he took his motorcycle and headed south where he graduated from candy bars and blankets to Scotch whiskey and, finally, gems.

"On our way back north, my partner at the fime, Chris Boyd, and I met an Australian opal miner in Brazil who got us for $400 worth of stones," he recalls, smiling at his naivete'. "We made our money back selling them in Venezuela, which was in its heyday at the time, because I think people there took pity on us."

In 1982, Green and Boyd went back to Brazil, this time with two new Honda motorcycles. Their intent was to sell the bikes, use the profits from the bikes to buy rough, have the rough cut into finished stones, and sell the finished stones for a profit. They were successful beyond expectations, and Green never looked back.

"I wanted to keep my costs as low as possible, so I found a cutting shop in Mexico. They were pretty good to start, but they had a lot of problems with polishing. I groomed them and helped refine what they could do, and I set them up with modern faceting machines. I've been working with the same four guys for 18 years now. For a long time, we cut all kinds of stones and every once in a while I would get back some briolettes, but I never thought too much of them until later."

By 1987, Green was immersed in a different pursuit. Shirley Maclane was on the cover of Time magazine with a quartz crystal specimen and the crystal craze was red hot. Green was also hot hot on the trail of Vera Cruz amethyst and other local specimens.

Around 1990, when the crystal market fell as quickly as it had risen, Green gravitated back to faceted stones. "The huge market for minerals shifted from the healy-feely holistic crowd to museums and collectors," Green recalls, "and that made it very difficult to sell medium-quality crystals. Fortunately, I'm one of the few people who has both legs and an arm in lapidary, and gem and mineral dealing, so as necessity dictated, I began to look for something unique."

RETRO RENAISSANCE. That something unique turned out to be the briolettes, and if there is something of a briolette renaissance going on it is due partly to Green.

Is it some sort of nostalgia trip? Probably not - it was never that popular to begin with. More likely, Green says, the popularity of retro gem designs is part of a back-to-the-future movement driven by what many believe is a saturated market where niche marketing is the key to success.

If that's true, Green still had one problem to overcome: setting briolettes with conventional settings was clumsv and inefficient. After refining their shape, calibrating sizes, stocking off-beat materials, and carefully matching pairs, a reliable system for mounting the stones, which has always been their Achilles heel, remained elusive.

"People always asked me, 'Do they come drilled? How do you set them?' That was always a problem. And they didn't always like my answer. Glue, or 'adhesives,"' he corrects himself "is still a dirty word."

A lot of the problems people had with adhesives were due to a lack of information, a problem that Green set out to correct. "People were trying to glue onto a polished surface. They were using the wrong adhesives, or notching the stones and running into trouble with cracks, so I wrote a paper called Briolette Adhesion Techniques that I give to people. It's not rocket science, just an outline of what is needed to achieve superior bonds. Anyone who works with glass already knows that surfaces should be clean and etched with an air-abrasive tool, and I offer the abrasion service. I've heard that an etched surface has 7,000 times the surface area of a polished one.

Green also developed an inventive line of calibrated caps to set the stones. "People didn't have the experience or the ability to make tight-fitting caps, and it's not because they weren't good metalsmiths. The problem is that the top of a briolette is basically a cone with a constant angle, and to get a good bond, you have to fit the top almost exactly to the cap, and that's a lot more difficult than you might think."

Green ended up drawing a set of blueprints and going to a machinist to have them milled.

Jewelers can buy a set of the master caps in a range of angles, to match almost any briolette. In retrospect, Green says, "It's a simple thing, making caps, but some jewelers don't take into account the mechanical aspects of the job. One size doesn't fit all."

It's one thing to design a new/old stone, and quite another to create a new system or family of stones, and that's what Green has done- In a way, Green is doing for the briolette what Bernd Munsteiner did for fantasy-cut stones. They are a different kind of gemstone, presented differently, and Green is bringing them into the 21st century.

Not only are the versatile stones and precision caps easier for jewelers to use, they also permit the stones to be used in a modular fashion, even to the point of interchangeability. Otherwise the briolettes appear much as they have for hundreds of years.

"The fluidity of their motion along with their natural shape make them uniquely beautiful, but familiar at the same time. Whenever I see someone wearing them I always notice their movement they wiggle, swing, and dangle. And the shape is natural, like a raindrop on the end of a leaf. It's a much more familiar shape than, say, a round brilliant that you would never see in nature.

"The unique look, the history and the familiar shape give them a pedigree that predates other stones. When you combine all that with their quality, versatility, and affordability, I feel they have a brilliant future in store."

(Return to the top of this page)

Briolettes Enchant Modern Day Consumers

by Cheryl Fenelle for retail.com, Jan 12, 2001

Retail.com,

Briolettes are found in the crown jewels of many royal families, including the Austrian dynasty, the Romanovs of Russia and the royal and Napoleonic houses of France.

In the "old days," when detail and elegant beauty took precedence over flashiness and efficiency, diamonds and gems were artfully cut with many facets. Some of the more popular historic cuts included the old miner's cut, old European cut and briolette, or drop cut. Briolette is found in the crown jewels of many royal families, including the Austrian dynasty, the Romanovs of Russia and the royal and Napoleonic houses of France. A diamond briolette necklace given by Napoleon to the Empress Marie Louise is on display in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Gradually, modem cuts, making the most of the material and often assisted or cut completely by machine, took over. But briolette gems have come back into fashion in a big way. Recently at auction, a pair of red tourmaline briolette earrings with amethysts that belonged to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis sold for $35,000.

Today's definition of a briolette cut gem is an inexact one. The dictionary describes it as "a pear-shaped or oval cut gem cut with triangular facets," though designers have taken liberties to deviate from the standard.

The theory for the gems' success is varied: some put forth the opinion that the public has a renewed appreciation for history, hand Grafted quality or for antiques. Others maintain that consumers just want something different.

"People want classic and retro-type jewelry. A lot of pieces are made the same way now as they were years ago. Some of the hottest items look as though they might have been in a vault for 60 years," said George Press, president of George Press Fine Jewelers in Livingston, NJ.

Briolette cut was popular in diamonds in the 1800s, and though some briolette diamonds are used by designers today, the gems most commonly cut in briolette are semi-precious colored gemstones like amethyst, aquamarine and peridot. Ruby, sapphire and emerald are cut in briolette, but they are not as common because rough, uncut material is more difficult to get, according to gem cutter Steve Green of Rough and Ready Gems in Littleton, Colorado.

Briolette cut stones are relatively available though they are more limited in supply than commonly faceted gems simply because there are fewer cutters. The gems can be cut by hand or machine, but both methods require years of experience and skill.

The dazzling effect of the faceting adds a unique look to jewelry. The shape of a briolette lends itself well to a pendant or dangle, but because they can be mounted several ways, designers have lots of room for creativity.

According to Green, briolettes are mounted by either drilling a vertical hole in the top of the briolette and adhering a pin into the hole; cross-drilling horizontally through the top of the briolette allowing the briolette to swing freely on a wire or pin; or abrading the briolette tip, preparing the gems outer surface for bonding into a cap. Epoxy adhesives are used to adhere the cap to the gem.

Unlike brilliant cut gems that maximize the reflection of light from

the table, briolette cut gems are designed to be viewed from all angles

and have a more quiet glow. Adding several pieces to your jewelry

display will surely spark interest, as well as sales.

(Return to the top of this page)

Drops of Light

by Doug Graham, Colored Stone Magazine, 2001

They may be enjoying a modern renaissance, but briolettes have a history that stretches back 800 years and across several continents.

These pear-shaped, multi-faceted gemstones arrived in Europe via India early in the 17th century. In those days, the West lagged behind much of the rest of the world both culturally and technologically. Everyday amenities such as indoor toilets were not yet commonplace (Elizabeth I of England was one of the first European monarchs to have regular access to a "water clos- et"), and luxuries such as spices, silks, and gems were highly coveted by aris- tocrats and landowners with a lot of cash and little or nothing to spend it on at home. The briolette immediately caught on with this moneyed minority, and in the centuries that followed the cut was conspicuously donned by some of history's most prominent figures among them Louis IV, Catherine the Great, and Marie Antoinette.

Once considered "cutting edge," the briolette became passe with the coming of the Industrial Revolution. New cuts, most of them ancestors of today's table-crown-pavilion styles, were introduced by economy-minded jewelry makers, who considered the briolette an inefficient use of gem rough. The Victorian age witnessed the revival of the briolette, but by the mid-20th century it had gone underground again, a victim of Depression downsizing and modem manufacturing methods.

Now that we have finally arrived in the science-fiction future envisioned in the 1950s and 1960s, we are looking back, and the briolette, like many things old and elegant, is popular once again. Wholesale gem dealers from Manhattan to Manhattan Beach, California, are seeing interest in this historic cut. Los Angeles-based Omi Gems proprietor Omi Nagpal, for example, reported a strong positive response to his offering of matched sapphire briolettes at the re- cent gem shows in Tucson, Arizona.

"We got a very good response from buyers at the show," he says. "All they're saying is, 'Can we buy one?' I think that's the next [big] thing."

Pramod Kotahwala of Universal Gem Traders in New York also reported strong interest in briolettes of multicolored sapphires.

The key factor in their popularity is their unique look. "If [customers] want exclusivity in something creative, they have to pay extra. Creativity has be- come very important nowadays," Ko- tahwala says.

The appeal of briolettes for jewelers is not just their look, but their versatility as well.

"Briolettes are great for special occa- sions," says Nina Ellwood of Bead Atti- tudes Inc., a maker of jewelry and bead- ed lace in Atlanta, Georgia. "They work really well as earrings and pendants be- cause they dangle and catch the light. They are unencumbered by any setting except at the top, allowing you to see more of the gem than with other cuts.

"Briolettes also have a very wide appeal," she adds. "Some people like them because they're dressy, others because in some ways they're more stone than jew- elry. Quartz and amethyst briolettes are especially popular with New Age folks, who believe the crystals have healing powers which are intensi- fled when cut into a briolette."

A different look requires a different cutting method, and briolettes have their own peculiarities.

A briolette has no table, says faceter Meg Berry of Pala International in Fallbrook, Califorma, who won a Cutting Edge award for tourmaline briolettes last year. Instead, the cut can be viewed from any direction, with no direction providing a better view of the stone than any other.

Briolettes have a different mission from more standard cuts, whose beauty largely depends on the degree to which they reflect light. By contrast, briolettes are supposed to possess an intrinsic beauty independent of their ability to return light to the eye. The difference is subtle. Berry says, but it has a big im- pact on the way briolettes are cut.

"The cutting technique is harder with a briolette because there is more free form," she explains. "When working with a regular stone, you have parame- ters to follow, but with a briolette the pattern is set by nature. I use no spe- cial tools or handling equipment, but because of the shape, cutting skill is a big issue, especially when making matched sets. Everything you did on the first briolette has to be perfectly duplicated on the second. Holding a stone on the wheel for just five extra seconds can throw everything off, and the repercussions go all the way up the stone because you're dealing with a lot of long, thin cuts. Every mistake you make is magnified over much larger areas [with] a briolette than with a round stone. You have to know what you're doing to do it well."

Steve Green of Rough & Ready Gems Inc., a lapidary and briolette specialist in Littleton, Colorado, agrees with Berry's assessment. He says that briolettes are more difficult to cut than standard stones, because the facets are placed on a larger number of angles. This requires cutting parallel to the wheel, which can prove very tough since some machines aren't large enough to cut the facets that run along the length of the gem.

Accidents will happen unless the job is approached with greater-than-average skill. A long and thin briolette, for example, can easily pop off a dopstick. Accurate drilling can also be a challenge, since the briolette's tip presents a very small "target" surface area on which to initiate the hole.

The cutting machines employed by Green's staff of six are all modified from basic models. Key to the operation is an ultrasonic drill, which is designed to put small-diameter, accurate holes into extremely hard materials. The drills are very hard to get in the United States, Green says, since most are made for strictly technical applications and cost as much as $100,000. Fortunately, less expensive models are now made in Taiwan and Japan that are specifically designed for lapidary use.

"The briolette has been described as 'lunar brightness,' as opposed to the more dramatic brightness of the sun," Green says. "It's more romantic than overpowering, which makes it kind of out-of-place in this day and age when everything has to be super-efficient and streamlined. One of the great things about briolettes is that they make relatively inexpensive materials appear elegant. That is not to say you can't use costly stuff, only that it isn't absolutely necessary. Lively and colorful is the criteria you're actually looking for, which means that you can use sapphires, tourmaline, quartz, or nearly anything else." He makes briolettes from over 50 different materials, everything from aquamarine to green beryl, heliodor, Mexican fire opal and even dinosaur bones.

Durability is a big plus, as soft or brittle materials run an increased risk of chipping and other damage.

Rough and Ready briolettes range from 6 mm to 40 mm in length, and 3 mm to 15 mm in diameter. Most have a round cross-section, though a few are made with an oval cross-section, the latter breed being slightly flattened and almond shaped. Wholesale prices for most faceted briolettes Rough & Ready's prices and size range are typical throughout the industry, although it still isn't common for gem dealers to carry briolettes at all.

Despite their popularity, briolettes are not usually mass-produced. According to Green, Berry, and others, discount stores do not often trade in them, and many jewelry stores won't sell them unless they employ a custom jeweler on site.

(Return to the top of this page)

Prior to my briolette business, I was actively involved in mining the world famous Veracruz amethyst locality. Read about some of my exploits and adventures here - Steve.

Las Vigas, Veracruz Mining Memoirs

by Steve Green

Reprinted from the Nov/Dec 2003 issue of Mineralogical Record

My first contact with Veracruz amethyst was back in 1981, during a gem sales trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was in a holistic massage-aroma therapy rock shop with the incense burning and the Indian silk images of Buddha hanging that I first saw these beautiful well-formed purple crystals. I listened carefully to the proprietor and decided that a trip to Las Vigas de Ramirez was easy enough for me. I spent my youth growing up I Mexico City, I knew the country very well, and my Dad was still living in the Distrito Federal. This made for a perfect combo for my future amethyst ventures.

Extra Fine Veracruz Amethyst on Matrix.

Only a 4-hour drive from Mexico City, the old run-down town of Las Vigas served mostly as a transit point for hundreds of campesinos who populated this vast area of 8000-foot deep barrancas and 11,000-foot tall ridges. Perched high on the edge of this mountainous area, between the central plateau and the precipitous drop-off to the Gulf, Las Vigas was just off the highway to Jalapa ( Xalapa). It served as a gateway to the more modern cities and markets of Mexico for the mountain people of the region. Las Vigas is situated on one of the main roads from the gulf coast to the central Mexican plateau. It was near here that Cortez and many others found a passable route into the interior centuries before. Only 50 miles to the south rises the glacier covered 19,000 foot Citlaltepetl or Pico de Orizaba the third highest mountain in North America. Products like cheese, wood, marble, milk & livestock were brought from the sierra and sold in Las Vigas. A constant flow of buses and trucks clogged the centro. Dropping off and picking up people and goods coming from or going to the remote mountains that lay beyond. Supply trains of mules and donkeys were loaded with kerosene, batteries, clothes, beans, pots, radios, cookies, candies, refrescos, beer, televisions, tools etc and taken into the sierra to be sold and resupply the many people scattered within this roadless area. Although remote there was a thriving economy in the rugged mountains beyond.

There were also a few savvy merchants who dealt with the more obscure and esoteric (to the locals anyway) amethyst. Ever since the late 70s amethyst was like gold in these hills. It was possible to get rich if you hit it big. The average wage in this area was $3 usd per day or less. A good amethyst pocket could yield thousands of dollars of specimens. It remained obscure to many though, and only an elite handful of men worked with it back in 1981. Of course there were other ways to get rich too - the opium (goma) trade was there too.

View from the mountains near Piedra Parada.

It was Alfonso Ontiveros whom laid much of the initial groundwork for the amethyst business in Veracruz. The three Ontiveros brothers were from Queretaro. One of the brothers Manuel moved to the El Paso area while two other brothers stayed in Queretaro. Eugenio Ontiveros mostly worked the opal fields near his hometown while Alfonso Ontiveros traveled Mexico looking for and developing mineral specimen deposits and selling them to his US based brother. Thus the foundation had already been put in place when I arrived on the scene. In 1981 there were just a few families that sold amethyst in Las Vigas. They had a good working arrangement with their mountain relatives who brought it and left it on trust to be sold in town. This trust system remained in place for years and worked very well. Few if any of the actual miners had a clue what their amethyst was worth. The miners had families, livestock, crops and houses to tend to in the mountains. They could not wait around Las Vigas during the long periods before buyers would sporadically arrive. Thus they would leave their lots with trusted individuals in Las Vigas. There were no telephones in those days, only the local telegraph office. Communication was by word of mouth or letter and took time.

In the early days of my travels to Veracruz I was very lucky. Some very fine large parcels of good size matrix specimens came my way. It was way back in 1981 or 82 that I had my entry into the "serious" world of mineral collecting when John Shannon and Richard Kosnar came to my little apartment in Denver. They came to see a magnificent lot that put me on the mineral collecting "map". From this point on, I managed to get a few good lots every year. I still can remember some of these spectacular parcels. There was the one composed of hundreds of very aesthetic flowers on green epidote, cabinet size pieces that I sold to Marco Schreier. Another fantastic lot of the best grape jelly colored xls I ever saw that I sold to Ken & Betty Roberts. Many of these pieces were photographed for magazines and even made it to the cover of the Mineralogical Record. There were also many many fine pieces I sold in the Desert Inn Rm #212 or at the Munchen Mineralientage Show. The Veracruz amethyst business was exciting and rewarding back then. Fine material was coming out for reasonable prices and I had a good time in Veracruz.

It was in 1983 that I was first shown some unusual, different and sparkly crystals on matrix from the same sierras of Veracruz. Identification proved these to be andradite garnet from brown to green in color (demantoid). Being young and adventurous I put together various expeditions into the sierra with my friend Chris Boyd in search of this material. Remember, the USSR was still in existence, and the only demantoid garnet deposits known at that time were locked up within its borders. Demantoid gems were very rare and expensive in the USA at that time. It seemed that there could be a fortune in demantoid waiting for us in them thar hills.

Mountain folk near Piedra Parada.

Armed with a Pionjar drill, a case of dynamite, 2 mules, a sack of beans, and 3 local Mexicans we headed off for 2-week treks into the hills. It was during these treks, before any of the roads were built that I got my first glimpses of the remote country where the amethyst and the garnet deposits were. The trail into the backcountry from Las Vigas was well transited but impassable to vehicles. It wound along the tops of the mountains through 80-foot tall pines. It was an 8-hour walk (28 kms) to the community of Piedra Parada. Situated high within Tierra Fria (Cold Land), this small village is the center of the amethyst digs/mines. Back then there was no electricity, no communications, and no motor vehicles. This small town existed between the 19th and 20th centuries. The people here were not what one would expect. There were many blue-eyed, blonde, fair skin campesinos. (I heard that they were descendants of the French rulers of Mexico.) Their bare leathery feet, uncombed hair, and soot soiled farm clothes were evidence though of the hard lives they lead. It took some time to get used to seeing blonde blue eyed farm girls in smoke filled timber houses making tortillas by hand. Very reclusive and not used to strangers the women and children would run into there homes and shut all the doors and shudders upon our arrival. This was the norm, not the exception. The men were often away from home working the fields, which were precariously perched atop mountain ledges.

The andradite deposits occurred throughout these mountains, but at a much lower elevation than the amethyst. Having heard of a place where bowl shaped specimens solely made up of transparent demantoid crystals occurred, we began to make our plans. The stories and descriptions were very intriguing. In order to get to this demantoid locality it would be necessary to walk for another day beyond Piedra Parada to La Concordia. This required descending approximately 8000 feet into the barrancas below, crossing the tropical rivers in the bottom and climbing about 2000 feet back up the other side. This was Tierra Templada (Temperate land), a warmer lower zone where bananas and coffee grew. From here you could stand and look across the deep canyons to the high ridges above and see where you had been the day before. In a straight line it was maybe five or six miles, but walking it was about twenty miles of the steepest deepest terrain I have ever seen. Complete with coralillos (coral snakes) and tigrillos (small spotted cats).

With us we had Modesto, one of the 33 offspring of one of the 3 wives of Don Justino who controlled (owned?) the entire side of the mountain. As we made the final 2000-foot climb to the demantoid locale we would pass through small fields of opium poppies tended by Don Justinos children. Slit and scraped for the raw opium, the whole scene was very reminiscent of photos I have seen of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Luckily Don Justino liked us. He thought Chris looked like Jesus, and my fluent Spanish allowed me to put him at ease. I found Don Justino to be a very intelligent, well manner man, albeit with one illegal source of income.

Once our mining began Don Justino put out the word that no one should pass beneath us. This was good since our blasting on the steep mountainside would send hundred plus pound rocks plummeting through the forest for thousands of feet to their ultimate resting spot in the river below. The skarn we were mining in proved tough and tenacious. We did find a few pockets filled with loose demantoid crystals and the famed green bowls. These were quite unique and of high quality. One was sold to through Buzz Grey and Tony Kampf to the LA City and County Museum. Another very fine example went to John Barlow, and was resold many years later by Brian Lees. Bill Larson and Buzz got nice small ones too. These demantoid bowls are unique in the mineral world, maybe too unique since we only found about 5 or 6 of them. We did facet numerous sub carat stones, which the GIA certified as demantoid. Some even had their own unique and distinctive variety of coarse hollow tubules resembling the traditional "horsetail" inclusion. We managed to sell some of these cut stones and still do to this day, but the demantoid business never proved as economically successful as the amethyst business. Thus we only made a few trips to the La Concordia demantoid local.

Our treks into the backcountry lead us past many amethyst digs. (Amethyst being the "mainstream" stone was all spoken for and mined exclusively by the locals.) The amethyst deposits were only located in the top third of these high mountains within the 8000 to 10,000 foot range. Two to four men with nothing more than hand tools would work small deposits in remote vertical faces of the mountain. Breaker bars, sledgehammers, picks and chisels were the most readily available tools. If dynamite was had the blast holes were made by hand. It is an arduous task to make a 1 inch diameter hole, 2 feet deep in solid rock with nothing more than a chisel and hammer. A drill would facilitate things and guaranty a percentage for the drill owner. Drills and dynamite were always in high demand and short supply. I lent my drill numerous times in order to insure a supply of amethyst. If the deposit warranted it was open pit mined until the vertical face created above became dangerous and difficult to continue working under. At this point, depending on the deposit, small narrow tunnels might be dug, or the mine abandoned. I heard of deaths on numerous occasions due to tunnel collapses. The vertical nature of the terrain and the limited equipment made many mines unworkable after awhile.

Most of these mines were on Federal land and operated clandestinely. There were a few mines that were owned and operated by organized outside efforts with permits. They were normally short lived and despised by the locals whom felt cheated out of their rights and amethyst by these outsiders. An outsider who came to this area and tried to mine would run into severe resistance and subversion from the locals. The illiterate local landowners were also cheated with deceptive contracts and false promises by Outsider amethyst miners. I personally read contracts that the trusting locals had signed that basically gave away their mineral rights in perpetuity in exchange for nothing. Lots of these sort of scams were tried on these people. Thus was the "game" in Veracruz. It was either the locals stealing from the bigger mine owners or visa versa, and amidst all this some fine amethyst would find it way to market.

Seasonally the Mexican army would do campanas into the area. Looking mostly for drugs, they would certainly bust you for explosives, mining, lack of proper papers, or most anything else they could dream up. The army could show up on foot or in helicopter. We never had problems since the "grape vine" was extensive and everyone knew where they were days well in advance. Their helicopters would also echo thru the canyons for miles prior to arrival. They did however make it difficult to blast on occasions since the sound would give you away for miles. The weather would also bring mining to a halt. Often shrouded in fog, heavy clouds, and torrential rains these mountains would become impassable for months at a time during the rainy season. All mining would come to a halt then.

Some of my Veracruz buddies. (Note gas cap.)

With the word out of our explorations and interest in different minerals we were constantly being shown new things. It was not long after that we were brought a small sample of a chrome green mineral. Off we went again in a new direction through the equally steep vertical world of these sierras. Hoping to find the elusive chrome green variety of Andradite we toiled for days at a new locality on land owned by a very serious man with big facial scars. He had been recently released from prison for murder. We never felt very comfortable at this locale and called it quits after two short trips. We did however find some very nice vesuvianite crystals in this area. (Initially we thought they were andradite.) Locked solid within an amorphous calcite matrix they often required acid to expose the vesuvianite crystals. We never did find more of the chrome green mineral.

It was in 1986 that the metaphysical craze hit in a big way. This drove up demand and prices for the loose amethyst crystals. Although the serious mineral collectors scoffed at this craze it fueled the search for amethyst in general. Ultimately leading to the discovery of many more fine pockets of amethyst specimens and loose crystals. Prices for specimens and loose crystals reached new heights, but the demand was very strong and supported this phenomena.

The hey-day of the metaphysical market and other circumstances kept me form making many treks into the backcountry after 1986. It was fun while it lasted, but the dangers far outweighed the rewards. Thus I stuck to just buying in Las Vigas and Piedra Parada, along with some financing of mining amethyst operations. Next the government widened the trail to Piedra Parada making a 4wd dry-weather-only-road and detailed information about Veracruz amethyst was included in articles and books. (Partly due to my contributions to Werners Liebers amethyst book.) This brought new and more buyers further into the backcountry. More and more the "secret" was out on where to find this magnificent material. Gradually business changed, and the middlemen in Las Vigas were cut out. Now the miners wanted to sell direct. But, they were not centrally located and spread all over the mountain. They were not in secure areas as bandits were a constant fear. They were not experienced or educated, and often asked ridiculous prices for low-grade material. No longer was the amethyst easily accessed just off the highway for a select knowledgeable few like myself. It was becoming necessary to travel the 4wd road to Piedra Parada. This was becoming the new amethyst central.

The holistic craze lasted until about 1989 when it quickly went bust and along with it so did much of the mining and further exploration in the area. Sure, there was still amethyst coming out, but with depressed prices on the loose xls it was necessary to ask even higher prices on the specimens. This hurt the demand, which in turn hurt the supply. This was a deciding factor in what I consider the downward spiral of the Veracruz amethyst business. The few over priced top quality specimens were not enough to pay for the operations. Especially since the lighter specimens and loose crystals were no longer marketable.

Slowly prices continued their upward spiral, while collectors only wanted

the best. The market for mid to low grade disappeared. Crime and corruption

was up all over Mexico and the paranoid government made explosives near

impossible to get. Many newbies in the business paid ridiculous prices only

forcing the prices up further. Profits were being squeezed out and the time

had come for me to say good-bye. In the past 10 years I think I have only

been there two or three times. By 1995 my first son was born. The market to

sell amethyst was difficult. Only the finest specimens were in demand. The

medium grade and loose crystals were nearly unmarketable. It was around 1992

when I stopped making regular trips to Las Vigas. On occasion I do ask some

of the Mexican mineral dealers about the area and get some news. Usually it

is bad news, and reflects the lawlessness of the place. The last news I had

was from Mario Viscarra when he told me that the son of a Las Vigas friend

was found dead hanging from a tree at one of the amethyst mines! The dangers

of the area take on new meaning to me now as a husband and father of two. I

pretty much quit going and I'm generally unaware of the current situation.

I made many wonderful friends and had fantastic experiences with the people

in those hills. Maybe someday I will go back.

Copyright Steve Green - Littleton, CO

(Return to the top of this page)